Note: I wrote and published this piece last November. It says most of what I could ever think to say about Thanksgiving, and tradition, and all sorts of other things. So instead of trying to churn out a few thousand more words this time around—especially since it’s a holiday week—I’m posting this one again, since I can now record audio versions as well. There will be some fresh newsletter content coming down the pipeline soon, I promise.

How would you act if you knew you were about to do something you loved for the last time? Most people never get a chance to find that out with any kind of foreknowledge or certainty.

Not so for Canadian-American rock group The Band, who played their final concert knowing it was their final concert, and even got their pal Martin Scorcese to come film the whole thing. On Thanksgiving Day 1976, The Band—Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson—played for more than four hours at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, joined by a whole host of friends, from Bob Dylan to Joni Mitchell to Van Morrison to Ringo Starr. These other luminaries helped send them off in style, recording some of the most cherished versions of The Band’s songs—and their own.

This concert film, augmented with a few songs The Band played with Mavis Staples and the Staples Singers on a soundstage the following day, became The Last Waltz, a one-of-a-kind documentary still renowned for its beauty and its controversy.

I am neither a music critic nor a person of great depth and taste, so I won’t wax poetic about the songs themselves and all the feeling and meaning that they are imbued with. I think they can speak for themselves in that regard, and in doing so answer the question I posed above. At the end of a storied partnership this group rose to the occasion for one last night and absolutely blew the doors off, for hours and hours. There’s some magic in that.

(When my wife and I were sending out wedding invites, we encouraged guests to request songs when they RSVP’d. “Caravan” was my dad’s choice—to encourage high kicking on the dance floor, like Van did.)

Viewing The Last Waltz for Thanksgiving was a tradition in my house, at least as far back as eighth or ninth grade. The music and the reddish stage lighting are permanently and inextricably linked with the holiday for me, as much as the food or football or occasional guilty feelings about celebrating the day at all. What I didn’t realize until very recently is that it wasn’t just my family doing it. (Sort of silly to assume that the significance of the date had been lost on the rest of the world, but it’s just one of those things—you never know until you know.)

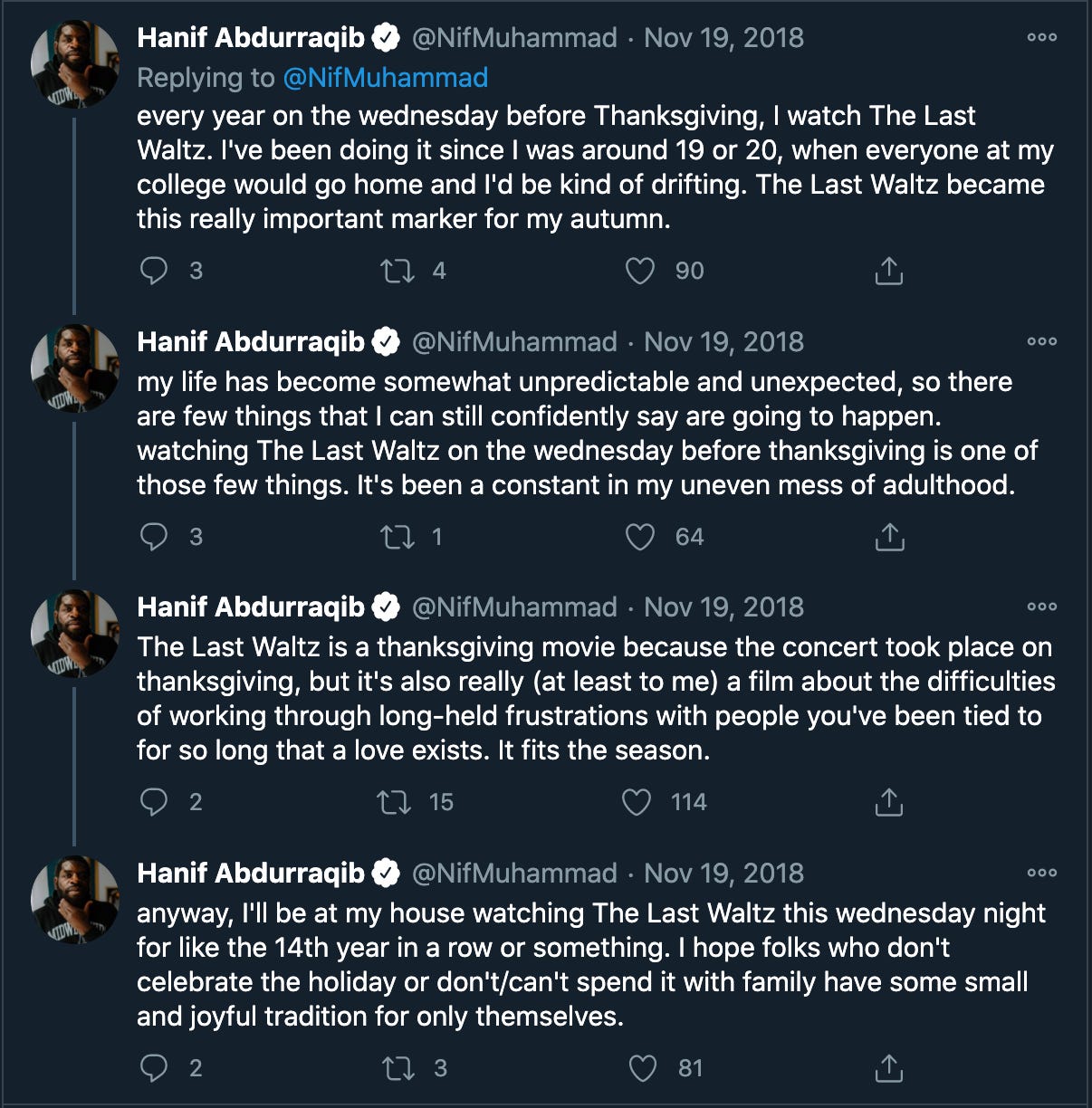

The poet and essayist Hanif Abdurraqib—who very much is a music writer and critic, and more importantly a fan—is one of those people who marks Thanksgiving with The Last Waltz each year. I thought his reflections about his own associations with the movie and the holiday were particularly sharp and poignant. (He also ranked all the performances from the concert, if you’re in the mood to argue with someone in your head.)

For many years, something I looked forward to on Thanksgiving weekend was the “Reunion Bowl,” a full-contact football game organized by my older brother and his friends that they were kind enough to let my younger brother and me, and eventually our own friends, join in on. It being Upstate NY in late November we were usually playing in the snow, the rain, or both, and every hit had the potential for chaos. I have never played competitive football and so never learned how to tackle, or be tackled, properly; the same was true for just about everyone else in that ragtag crew. The “penny on the train tracks” approach was the general method, especially if you were tasked with bringing down a bigger guy. Other than a few concussions (my own first included), there were basically no significant injuries in 10 years of the game, somehow—a player safety rating that Roger Goodell would kill for.

But despite that record, or perhaps because of it, the Reunion Bowl came to an end. (Not before getting written up in ESPN, though.) All good things must. We had invented our own tradition, and we had abandoned it on mostly our own terms. Our final game was no sold out concert, but we did know it would be our last, and even got hats made to commemorate the occasion.

Without it we are all left to make our own traditions, now that we have our own cities, our own friends, our own families. Those games exist now only in our memories, our blurry photographs, the stories we tell each other after a drink or five. I was happy to hear recently that many of the core guys from those games have adopted The Last Waltz as part of theirs, even if they weren’t raised on it.

Whoever and wherever you are, your Thanksgiving will probably look different this year, too. Some or all of those you hold dear are out of reach, yet I also sense a glimmer: that our sense of what we owe one another, how interconnected we all are, has never been keener. Your traditions and rituals will necessarily change in 2020, or at least be put on hold. So why not pick up a new one? You’re cordially invited to join my family and me in one of our most tried and true.

Catch a cannon ball now to take me down the line

My bag is sinkin' low and I do believe it's time

To get back to Miss Fanny, you know she's the only one

Who sent me here with her regards for everyone

I’ll catch you all next week. Stay safe out there—and remember, no one can make you keep your camera on during the extended family Zoom call.

-Chuck

They Say Everything Can Be Replaced